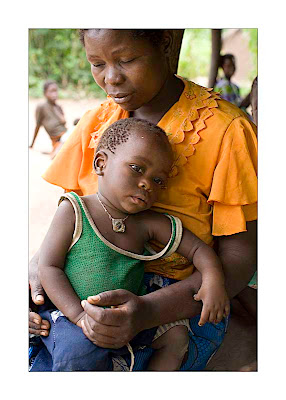

On Thursday last week, I met Sapuleni.

She came with her youngest son to a roadside clinic near "Chipolonga" where our team provides nutritional assessments and, if needed, "Chiponde."

Unfortunately, her son is quite sick with severe acute malnutrition (SAM).

At the clinic, Sapuleni received advice and a bundle of Ready-to-Use-Therapeutic-Food.

Fortunately, with proper treatment, her son his likely to recover.

Before Sapuleni left the clinic, we had a chance to speak.

Her spirit and warm energy stood out in the crowd of mothers that morning.

I asked her if she would allow me to visit her at her home.

Then, I explained my goal.

Through an interpreter, I told her I am working on a documentary project to support children who are hungry, children who live within families that need food and medical attention. I told her I am taking pictures to communicate how clinics such as the roadside program she attended impact family's lives in Malawi.

I tried to explain that I want to better understand the reality of daily experience in a rural village - to touch the world she knows each and every day in an intimate way.

I asked her if she would allow me to bring my camera and sit with her and her family for a day or more during the weekend.

She smiled and let out a light laugh.

Yes, she must have thought, "here is a crazy azungu (white person)."

The notion of her daily life holding interest to someone from a far away place must have been both unusual and surprising. What could she possibly share?

I told her she didn't need to change or alter anything in her day. I spoke about authenticity and my desire to see her experience first hand in an unfiltered way.

After a short pause, she nodded her head and accepted my request.

As Sapuleni walked off in the morning light with her son on her back, I felt encouraged.

I planned to drive three hours early Saturday morning to meet with the chief of her village and then come to her house.

I did not know much about her family or her village, "Kwilasya," yet Sapuleni seemed to express much that I am drawn to with my photography work. She seemed strong, thoughtful, and expressive in her spirit.

In our first conversation, she shared a raw outline of the circumstances that led her to her son's health crisis.

She is very poor.

She has many children.

She has no food.

She has little opportunity for work.

All common challenges in rural Malawi.

I worked with one of the student doctors, a nurse, and a government health worker (a "HSA") to plan our visit.

After driving to her village from Blantyre, we picked up the local health care worker and drove to the chief's home. The chief was not available, but his wife provided permission for us to walk about a half mile on a small path through several fields of corn to visit Sapuleni's house.

By the end of our first three or four hours together, Sapuleni's life unfolded in bolder, more difficult, and more moving ways than I could have predicted.

I left our time together, torn up, moved, hopeful, challenged, worried, and inspired.

Here is a bit of Sapuleni's life story ...

* * *

At this time, Sapuleni does not know her age. This is common for many individuals who live in rural areas of Malawi.

It turns out, she has a very large family - nine children.

Here's the kicker. She is now a single, divorced Mother.

Her previous husband is a fisherman.

When they married, Sapuleni's parents provided the newlywed couple a small piece of sandy dirt to build a home and start a "garden" (think corn).

Sapuleni came from a Muslim family. Her husband came from a Christian family.

As you might guess, these types of mixed faith marriages are tough in any rural community, especially southern Malawi.

To support unity, she converted to Christianity at the time of her wedding.

Sapuleni and her husband built a one room house out of bricks and mud. For about seventeen years, they lived together in this small home and worked their way through tough times with bits of corn, fish, and vegetables as the primary source of food in their diet.

Sapuleni told me that "Hunger season," the period from about November through March, is always tough.

Unfortunately, when Sapuleni was pregnant with her ninth child, she became very sick. She had to go to the closest hospital, which is about ten kilometers from her home. There, she received medical care for about a month.

Since her family has no car or bicycle, communication with her husband and children was difficult during the time she was in the hospital.

After, she gave birth to her child, she returned home and found a surprise. She discovered her husband was sleeping with another woman while she was sick and away from the village.

This led to a series of heated conflicts.

Ultimately, Sapuleni asked her husband to make a choice - faithful marriage or divorce.

He chose divorce.

Suddenly, Sapuleni found herself alone with nine children, no education, no profession, no source of income, and few assets outside of a minor collection of old pots and pans.

To complicate matters, one of her children developed mental health issues.

The marriage separation took place about one year ago. Her husband left their home and ceased all communication and support.

Sapuleni's children are now 18, 17, 16, 15, 13, 9, twins at 6, and 1 year nine months old.

Her days involve constant motion and commitments of care.

Two to three times a day, she must walk about a half hour to get water from a bore hole with a manual pump. This, as you may guess, is not the purest of water sources. She pours several gallons of well water into a large yellow plastic can and returns home.

Her family's diet consists mostly of corn flour and boiled water. Sometimes, Sapuleni can sell bits of corn from her garden or find work in her neighbor's gardens to raise money and afford a bit of small fish and vegetables such as pumpkins.

Her previous husband he has not provided support of any kind. He still lives in the "hood," but his commitment to his first family, Sapuleni and all nine children, vanished completely when he left about a year ago.

The full family is now Sapuleni's sole responsibility.

To support her children, Sapuleni works in the only way she knows how to earn money - she provides manual labor in neighbor's homes and gardens.

Generally, she is paid 30 to 40 Kwacha (twenty to twenty five cents) per day for about eight hours of work.

Imagine this compensation as a means to support nine children. What a challenge.

On Sapuleni's best days, she makes about 100 Kwacha (sixty six cents).

With a day's wages, she can sometimes purchase one or two cups of milled corn flour for "Nsima," the primary source of food for her family.

Sapuleni has no brothers and no sisters. Her father passed away years ago. Her mother, who is about sixty years old, lives nearby in a small mud hut with a thatch roof.

So, there is no extended family to offer support.

Sapuleni's older children split their time between work and school.

They too make meager wages for simple manual labor.

As you may guess, it is difficult for Sapuleni to support her children in school.

Much like many other regions of Africa, Asia, and South America, there are requirements for uniforms and other fees in Malawi's public schools.

In some local classrooms there are over one hundred students - quite a student to teacher ratio.

Almost all teachers in rural Malawi are poorly paid and overworked. As a result, these professionals are sometimes far from sympathetic toward children who cannot meet basic requirements.

It is difficult to keep the poorest of the poor in school.

Quite often, Sapuleni's oldest son is thrown out of classes because he has no funds for simple class fees and no uniform. The fact that he needs to leave school early to work on many weekdays creates further challenges. Yet, Sapuleni continues to push hard for his education for all of her children. She believes this is essential for their future. Her oldest child, who is eighteen years old, currently attends second grade. He had to drop out and then re-enter school during the last year.

Poverty has a way of cycling deeper and deeper.

Sapuleni cannot afford fertilizer. She was not able to get a government voucher. So, her corn crop from the small plot of land around her house is weak and fragile.

I asked Sapuleni what her current feelings are about a large family.

She spoke about her love for her husband and all of her children and the evolving flow of life. She mentioned her experience with family planning. Through her years as a child and young adult, she never had any education in this area or understanding of this concept.

She wanted to be part of a large family.

She did not anticipate life would be so hard.

In Malawi, a large family is generally a source of wealth, blessing, and pride.

Unfortunately, the rest of her village is not in a position to offer support.

Each year, Sapuleni needs more and more food to support her growing children.

Through all her experience, even the rough moments, Sapuleni continues to have faith in God. She spoke about her beliefs and her hope that all will evolve in a positive way.

In may respects, Sapuleni's heart is tied to her children.

When she spoke about her dreams, her words were focused on their future.

Education is her main goal.

She described the importance of each child learning to read - a skill she never developed. At this point in time, only one of her children can read and write.

She spoke about the possibility of her children gaining employment. She yearns for this.

In a full year, Sapuleni's income is often only $30 to $50. Think about this. Her annual income is roughly equivalent to the cost of one dinner for one person at a restaurant in the United States.

Sapuleni allowed me to sit and witness her daily life. I encouraged her to act as though I was not present.

I filmed her making corn stew, cooking tiny fish, gathering corn, feeding her family, cleaning her house, and interacting with her children.

When I entered her home in the middle of the day, it was dark. Two small windows provided the only light. Within the brick walls, I found a barren slab of mud that serves as Sapuleni's floor, a few extra pieces of clothing, an old, broken, plastic radio that was dusty and tied with a cord, a few worn pots, several mosquito nets used as a shelf and a hammock, a wooden board that looked much like a old, abandoned door, and a small swarm of unidentified flying insects.

Outside of one worn, wooden chair, Sapuleni has no furniture of any kind. There is no bed and no kitchen in her home - she cooks outside on a small wooden fire in a thatch hut.

My experience with Sapuleni at her home provided an intimate "brush" with poverty.

She graciously provided an opportunity for me to see how she lived and how she cared for nine children with little material resources.

Sapuleni's life is truly tough. Yet, through our time together, Sapuleni expressed warmth, hope, and a sense of resiliency.

I never sensed any remote sense of blame toward others. Nor did I ever feel she held onto the experience of a "victim." She seemed calm and "present."

She seems to work her way through each day, one day at a time.

It is hard for me to imagine the uncertainty she must live with.

It is fortunate her faith is so strong.

As we left our time with Sapuleni our little team of travelers provided several gifts, bundles of beans, corn flour, sugar, and soap - all cherished and graciously accepted.

As we drove down a long dirt path near her village, many questions flowed through my heart and head.

How might we transform Sapuleni's family's trajectory?

I searched for a way to uplift her experience and create some form of sustainable income.

Is there a way to use a "micro loan," a gift, an investment in inventory or equipment to allow her and her family to transcend current circumstances? How might we allow her to grow more food or produce greater income?

I wondered if there are creative and cost effective solutions that can impact her entire village.

Ideas flowed.

We could purchase a hundred small "chicks" for about fifty dollars. But, how would she feed and protect these little birds? Between the wild dogs and other predators as well as a village of hungry people, it is unlikely this idea can work as well as planned.

We could create a maize mill in her village. This would be valued, but expensive and inefficient given the small number of families nearby.

Fertilizer? Even a single bag would make an extreme difference.

Cloth for hand made products? She would need to learn to sew. Who would her customers be? How would her goods make it to market? Wouldn't this continue her cycle of depency on poorly paid hourly labor?

We might provide funds for inventory to start a small vegetable stand on the main path near her village. Would any food and funding support just be consumed?

We don't have a solution yet, but we are trying to find a promising path that Sapuleni wishes to pursue. We want to drive our engagement from her needs and aspirations. We may involve the chief of her village in this pursuit.

A charismatic and engaged nurse, Rosemarie, who came with me to the village for my visit was moved by Sapuleni's story. She is serving as a local "bridge."

We raised a small amount of money. We plan to explore a range of alternatives. There is a bit of hope.

Sapuleni's story is the story of thousands of mothers in Malawi.

There are no easy solutions to the experience of extreme poverty and hunger.

I recognize that sustainable change for Sapuleni's family is just a "drop in the bucket" for this country's and this continent's needs.

Yet, I don't know where else to start. So often, when we wish to impact large human issues, it requires starting at an intimate level. In many cases, we can not get "there," to a new future, unless we build up the broken pieces of our existing, fragile foundation.

We can toss food and other short-term resources into this crisis. And, we may be able to create powerful healing - much like the outcomes of Project Peanut Butter. At the same time, it seems essential to enable truly sustainable change that comes from within Sapuleni's own home and community.

I am not at all sure how to achieve this. I can see problems with so, so many alternatives.

Almost all of the forty to fifty families who live near Sapuleni share her poverty and food shortage. Working through logistics and potential curruption, cultural challenges, training issue, potential jealousy and equity issues from other village members and related parties, and other concners will all play a part in determining if any support for Sapuleni can be successful in the long term.

Clearly, positive, long-term solutions for this community may involve a combination of many changes - micro loans, small businesses, improved farming and crop yields, more accessible and more effective education, infrastructure investments, technology, and improved family planning are all needed.

It is fascinating to reflect on what people who live in extreme poverty say when you ask a simple question :

"What change will bring the most benefit to your life?"

The four answers I hear most often here in Malawi are: roads, education, fertilizer, and employment.

Ok. There are few individuals who go straight for the"gusto." They simply answer "money."

Yes. Wealth, happiness, and prosperity are defined and achieved in many ways.

Despite Sapuleni's lack of material resources, she has many valuable assets.

My hope?

That the future brings brighter days to her doorstep.

I write from a small cafe in Johannesburg airport.

I write from a small cafe in Johannesburg airport.